Hear from Willier on the fulfilment that comes with solving scientific problems, her experiences as an Indigenous student in studying science, and her volunteer work to both mentor first-year Indigenous students and increase equity, diversity, and inclusivity in physics.

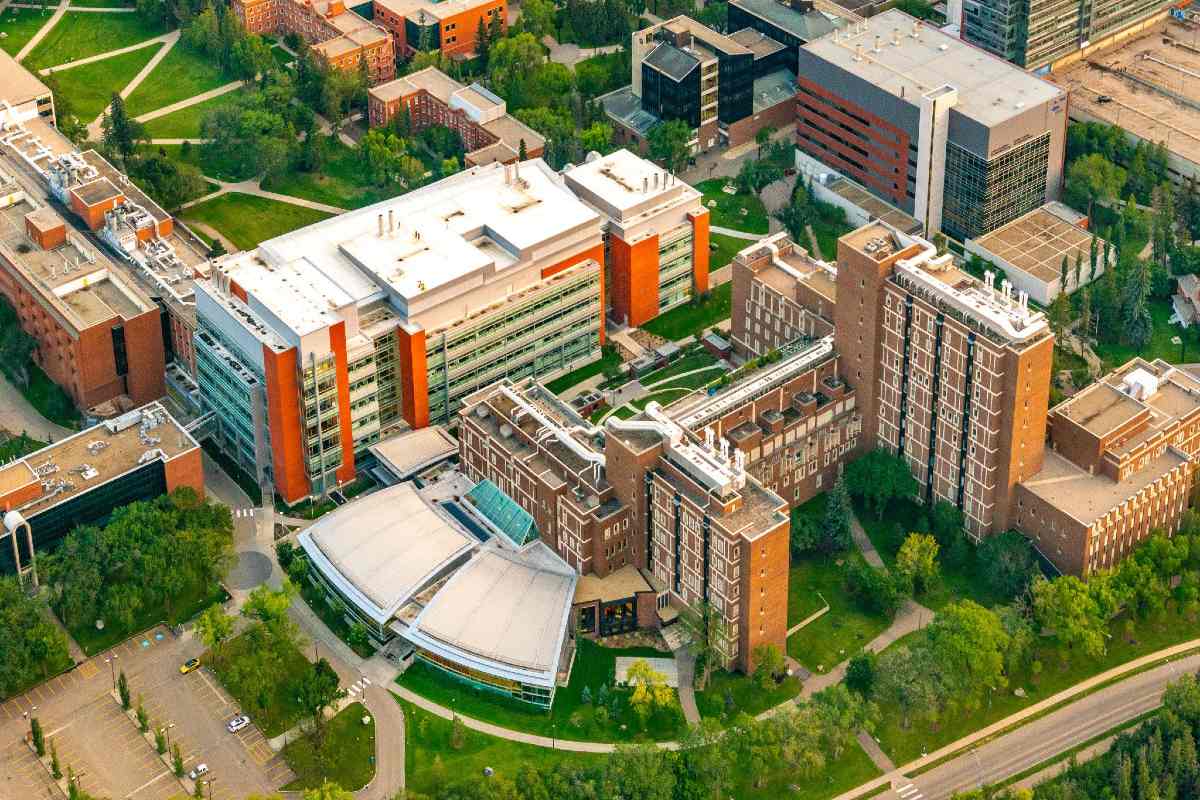

Undergraduate student Valerie Willier has long held a passion for science, mathematics, and the joys of learning. Her passion for the field has led her to pursue her undergraduate studies at the University of Alberta and lab work in the Department of Physics.

Hear from Willier on the fulfilment that comes with solving scientific problems, her experiences as an Indigenous student in studying science, and her volunteer work to both mentor first-year Indigenous students and increase equity, diversity, and inclusivity in physics:

Family is the most important thing to me, so as a young adult deciding where to attend university, I knew that I needed to stay close to them. I am Cree from Slave Lake, with a lot of extended family living in Edmonton, so deciding to attend the University of Alberta was a very natural and easy decision. Not only was it a great university, but it gave me the opportunity to stay close to my relations, close to the prairies, and to start my life in a vibrant research community.

I remember being in Grade 3 and deciding that I loved math and working with numbers, so science is truly a subject that has been important in my life from the beginning. I’m really grateful to have been raised in a home where education is prioritized, and I thank my mom and dad for gifting me curiosity about the natural world.

Science was always the subject that came easiest to me, and I loved the complexity and rigor of it all. I love calculations and analysis, and as I got to know myself throughout my teenage years, I discovered that I have an admiration for the strictness and exhaustiveness of STEM. Admittedly, this has sometimes turned into a bit of a love-hate relationship as I entered university level studies, but I have developed a real love for the learning process.

There’s something about working on a single problem for hours only to find yourself surrounded by crumpled papers of failed workings of a solution that is so amazing to me. Science has taught me to not only trust the process, but to also be proud of yourself when you finally get that answer at the end of the night, however late.

It turns out that I love this sort of intensity, and the key to capturing my interest is when I never run out of questions. It’s for these reasons that the abstract answers and theorems of mah continue to be a love of mine. This has really served me well during my time at the U of A and now, even years later, every class I take feels like a dream.

Experience as an Indigenous student in STEM

Firstly, I want to acknowledge that I have an immense amount of privilege being able to study at this institution, and I never take a single day of study or opportunity for granted. To be a student at the U of A who is able to consistently learn and explore whilst engaging with my inspirations around me—including professors, mentors, and fellow students—still seems too good to be true.

It wasn’t until my time in university, when I stepped into adulthood, that I began to understand myself and my positionality as a young Indigenous scholar. These days, I am overwhelmingly proud to be a Cree woman and to have the experiences in life that I do. They all shape me into being the type of scholar I am. Being Indigenous and being at the U of A showed me how to appreciate my own unique situatedness in this world and I am very grateful.

However, my time in STEM specifically has not been without its challenges. It has been tough to be Indigenous and to be in physics, to say the very least. As a field, physics is founded and built upon colonial ideals that prove to be materialistic, increasingly competitive, and impersonal, which turn out to be very poor qualities for an area that is bringing in marginalized people who don’t fit the stereotypical mould of who can do “the best science.”

I’ve often found it confusing for STEM fields to be recruiting members of minority groups to take on tokenized roles in programs, while those very programs continue to uphold those colonial power imbalances ingrained into the system. We need to be asking who our science serves—and who does it not serve?

I know that many times, the loneliness I felt in physics was unbearable. I’ve met one other Indigenous student in my program, and if it wasn’t for their friendship and kind understanding of our situation, I’m not sure if I would still be studying this subject.

Seeing an Indigenous person in physics is unheard of for some people, so many times people around me would dismiss my Indigeneity in the classroom or lab and my ethnicity would be assumed to be anything but Indigenous. This made me very sad, and I constantly felt out of place.

I’d hear the stories of famous researchers whose work has served science the best, and none of the greats ever looked like me—not even close. I try hard to be proud of myself and to make my presence known, however, it’s hard to do that when those around you assume that you won’t make it or that you’ll eventually drop out. I have had that assumption voiced to me a couple times.

In those moments, I remember those who have believed in me most who are members of the Department of Physics, such as my first-year professor Al Meldrum who gave me the inspiration to pursue physics and who pushed for me to get my first lab experience. At the end of the day, I am thankful to have this strength, but being Indigenous and in STEM has pushed me to show true resilience at school when I should realistically feel comfortable in my program.

Volunteering with the Aboriginal Mentorship Program

Indigenous peoples are often seen as unscientific and rather spiritual—but this notion that Indigenous peoples do not engage with science has been strategically crafted by the colonial project to further oppress us. As I said before, science is co-constituted with colonialism, meaning that western science is derived from European culture, much like how every science stems from culture.

“I want to let Indigenous students—and other non-Indigenous people—know that Indigenous people everywhere have the ability to not only do great things, but also do great science. There is a spot for you here, and the university is lucky to have you. You can achieve anything you set your mind to, and you will have plenty of help along the way.”

Now think back to Indigenous communities. If the very goal of colonization is to weaken our ties to our culture, our traditions, our stories, and our lifeways, doesn’t it make sense that our relationship with our science has also been weakened? The answer is yes. It’s not that we as Indigenous people are not scientific, but rather that our science is just different from that of settlers, and as a result, has been a target of colonialism.

Through the Aboriginal Mentorship Program, I get to talk to incoming Indigenous first-year science students about what opportunities are present for them at the U of A, as well as introduce them to the vibrant and courageous Indigenous community on campus. I want to let Indigenous students—and other non-Indigenous people—know that Indigenous people everywhere have the ability to not only do great things, but also do great science. There is a spot for you here, and the university is lucky to have you. You can achieve anything you set your mind to, and you will have plenty of help along the way. My main goal is to let Indigenous students know that although coming to campus may be scary and it may be difficult at times, the last thing you will be is alone, and the first thing you will be is resilient.

Improving diversity and inclusivity in STEM with UAP-JEDI

Being a part of the group University of Alberta Physicists for Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (UAP-JEDI) has helped me more than words can explain.

I remember receiving the very first email from group founder Lindsay LeBlanc on how she wanted to start an equity-seeking diverse group for members of the Department of Physics and I thought “Finally, a place where I can be myself.” Lindsay has been a true mentor and inspiration for me.

Through groups like UAP-JEDI and the American Physical Society’s Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity Alliance, I have started to see myself as a valid member of the physics community. Personally, it has been hard to feel like I belong in physics, and sometimes, I still don’t know if I deserve that seat in that lecture hall. It’s a complex mix of emotions, truly. It can be hard to feel like you’re not a fake when so many aspects of your identity are underrepresented in the community you want to be a part of.

I’ve done the research. I’ve taken the classes. I’ve networked. I’ve proven that I can do successful physics. And yet I struggle to feel like I’ve checked all of the requirements to deserve that sense of belonging. These are deep issues that are felt by many members of the BiPOC and LGBTQ2+ scientific community.

For these reasons, my favourite experience in physics so far was when I went to Toronto for the Canadian Conference for Undergraduate Women in Physics and spoke with other women there about our experiences. We’d have lunch and talk about our lives, our triumphs, our failures, and our experiences of imposter syndrome, all whilst showing the utmost empathy towards each other—and sharing laughs along the way. These are the real moments in the physics community that I miss and want to continue to have: genuine stories, genuine experiences. Human experiences.

Want to learn how you can get involved and increase equity and diversity—and combat discrimination—in STEM? Learn about the Engagement and Equity, Diversity, and Inclusivity in Science initiatives and resources in the Faculty of Science.