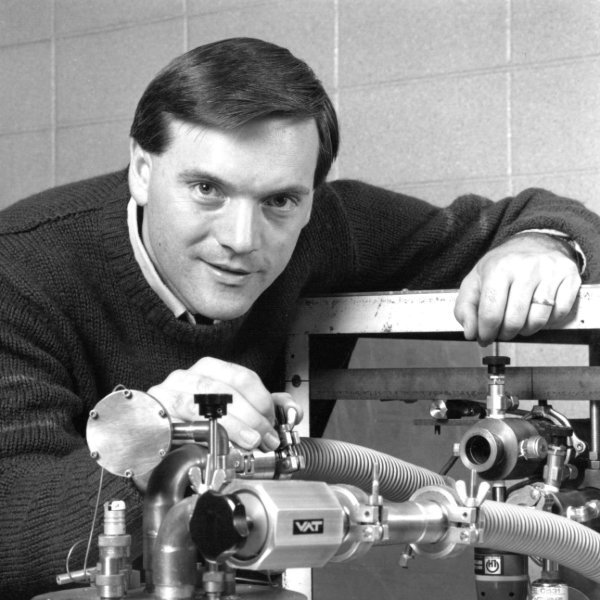

John Beamish, professor in the Department of Physics, reflects on his career of over 40 years. Photo credit: John Ulan

For John Beamish, professor in the Department of Physics, education didn't stop once he left campus as a student. In fact, the real life learning was just getting started, with each stage of his University of Alberta journey providing no shortage of personal and professional growth.

Beamish spent the 1970s as a student on campus, earning his undergraduate degree, his masters, and his PhD. Following a postdoctoral fellowship at Brown University in Rhode Island, he accepted a faculty position at the University of Delaware, a role he held for eight years, before the call of Canada pulled his growing family back up North, home to a professorial position at his alma mater, starting in 1991.

"Surprisingly little had changed since I left," said Beamish. "There hadn't been a lot of turnover. Most of the faculty I had worked with as an undergraduate and graduate student in the '70s were still here when I returned in the '90s. I worried when I came back that there wouldn't be any change or new hiring for many years and that I would be it for fresh faces. And for a few years, I was it, but then there was a lot of hiring, and that made all the difference to how you feel about the future."

Beamish reflects on Mark Freeman joining several years after he came, followed by a burst of hiring in 1996/97, with a focus of faculty in his general research area of condensed matter physics, including close colleagues Frank Marsiglio and Frank Hegmann. The momentum continued to grow, with Al Meldrum joining a few years later, with this strength in numbers allowing for the sharing of equipment and a flourish of ideas.

Better together, from fracture to focus

"For a while, it was only me on the horizon, but we just kept going, the whole condensed matter group, and it turned out to be very healthy."

As the largest generalized area of physics worldwide with thousands of groups around the globe, Beamish remarks that focused efforts have resulted in the University of Alberta's condensed matter group garnering international acclaim in the field. He says it is the dedication to working together that makes all the difference.

"It was a decent-sized group when I was a student in low-temperature and solid state physics, but it was absolutely fractured. We had some really good people, but almost nobody worked with anybody else, so the group had a lot less impact in the previous generation than it could have. When we started to rebuild the group, there was a plan, and we have built a really strong group that works together."

We are all physicists

Beamish reflects on one of the biggest shifts from his time as a student to his tenure as a faculty member, the union of experimentalists and theorists throughout the department, the latter of whom were formerly a group unto themselves.

He himself completed a masters degree in theoretical physics before transitioning into experimental physics for his PhD, reflecting his roots for a hands-on approach to the world.

"I grew up on a farm, which is not necessarily the best background to work in a lab, because you tend to break things. But as soon as I got in the lab, I realized the days where I broke something in the morning and fixed it in the afternoon gave me a great feeling of satisfaction. I felt I had a good day as long as it was in that order."

"I realized the days where I broke something in the morning and fixed it in the afternoon gave me a great feeling of satisfaction. I felt I had a good day as long as it was in that order." -John Beamish

From good to great

Though Beamish made the transition from theory to experiment, he notes the transition in the department to the inclusivity of both approaches to physics has shifted the group and the department from good to great.

"We are all physicists. This is a very positive difference."

It is Beamish's unwavering commitment to the physics field as a whole which steered his success as the chair of the department from 2004 through 2009. During his tenure, he was not only focused on strategic hiring, particularly in the areas of particle physics, astrophysics, and nanotechnology, with the concurrent creation of the National Institute for Nanotechnology, he also served as a key driver for the planning for the move of the Department of Physics from the old V-Wing Avadh Bhatia Physics Building to what would eventually become the Centennial Centre for Interdisciplinary Science, ensuring that the department's experimental work would remain strong in spite of physical dislocation for a number of years.

Beamish's reputation for excellence and collaboration made him a natural fit for his next role in the academy, vice dean, a role he served from 2013 through 2018. A self-defined introvert, Beamish is well regarded across the Faculty of Science for his warmth.

"Being a chair is a bigger impact in a smaller area. As vice dean, it is a very different role with a smaller impact albeit on a much bigger group of departments and people," he says. "I really enjoyed working with people across the science spectrum as well as the staff supporting our excellence in teaching and research. And working with the chairs was always great. We didn't always agree, but we always got along."

As for his approach for working with the chairs and the faculty, Beamish beams at an analogy. "When my daughter was ten years old and deciding what career to pursue, she said, 'I like to be useful.' She still says that." Beamish's daughter is a general practitioner in Hinton. His son teaches history at the University of Louisiana.

"The vice dean is like that. Being useful is a really big part of that."

Driving diversity in strategic hiring

Beamish's focus as vice dean was on hiring, and what he is most proud of in his tenure in that role is the shift in hiring practices in the Faculty of Science, a focus he championed alongside the Faculty of Science's stalwart champion of diversity, Margaret-Ann Armour, who passed away earlier this year.

"Working with Margaret-Ann was great. One aspect that changed over the years was the recognition about diversity in hiring. It wasn't that departments resisted, but they didn't necessarily think about it, and by the end of my term, the departments were all fully on board. They were all putting a lot of effort into diversity in hiring. The change in the hiring demographic is really positive. You can feel you've helped a lot. Margaret-Ann was a really big part of that and the departments too," says Beamish of the legacy that lives on.

When asked about his lasting legacy beyond the obvious impact on hiring practices across the faculty, Beamish chuckles and responds almost instantaneously: "Oh, the tunnel."

Committed to connection: the Beamish Tunnel

It was Beamish's dogged determination to keep the Department of Physics together between Phases 1 and 2 of CCIS that earned him some unofficially official signage on a tunnel connecting the two sections.

"We had to integrate CCIS phase 1 into the new building," recalls Beamish. "None of us with complex labs wanted to be separated from the rest of the physics department, so there was a need to connect at the basement level. But the tunnel was always on the chopping block due to cost. Every time it was raised, I said, 'Absolutely not. We agreed on this, and we are not fracturing the physics department.' At some point, I had defended it so many times, they just gave up. And on the day the building was turned over, the construction management crew had concrete-anchored these signs in there. That tunnel was only in there because I refused to let them cut it out."

Whether a tunnel between buildings or building bridges between disciplines, when looking back over a lifetime of learning, what comes next for Beamish after life in the lab and in the administrative chair? He's not planning on leaving the lab just yet, focused on working with undergraduate students and postdoctoral fellows in his passion for low temperature helium physics.

Beamish will be honoured this week with 40 years of super-solid physics, a tribute to his career.