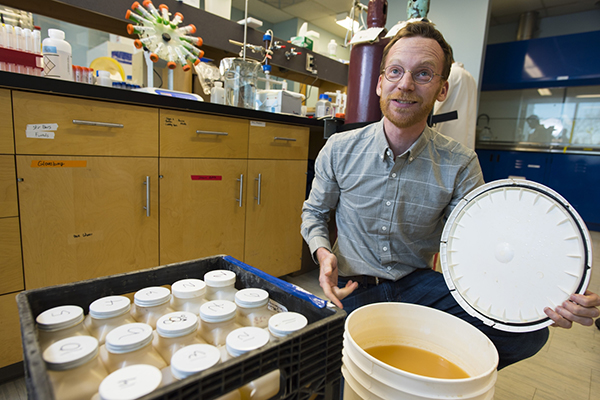

Dan Alessi, Encana Water Chair and assistant professor in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, examines flowback water as part of a $2M study to examine best practices in hydraulic fracturing.

Hydraulic fracturing has become a widely used resource extraction technology in today's world. Designed to increase the access to our petroleum reserves, this method has come under scrutiny in the recent past for its potential impact on the environment.

A University of Alberta scientist and his collaborators have received more than $2 million in research funding to fuel their search to inform best practices for hydraulic fracturing in Alberta. The research program is led by Daniel Alessi, assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences and Encana Chair in Water Resources, who joined the U of A in 2013, and aims to improve the water cycle in unconventional energy recovery.

Reducing freshwater use in hydraulic fracturing

"One of the things that people often worry about with hydraulic fracturing, unlike most other industrial processes, is that in many cases you're taking water from the surface and permanently removing it from the water cycle," says Alessi. "New strategies to reduce fresh water use, including treatment options, are needed from both an environmental impact and cost perspective."

The study aims to begin unravelling the chemistry and potential toxicity for flowback and produced water, to uncover sources of microbial biofouling in the water cycle of hydraulic fracturing operations, and to develop tools such as groundwater models to aid in the use of alternative water sources.

"Ultimately, we want to improve the water cycle and mitigate water use and the potential environmental impacts." -Dan Alessi

"The largest part of the project is to look at the chemistry, microbiology and toxicity of flowback waters," says Alessi, noting that during the process, a significant fraction of the fresh water that is pumped into the ground-treated in advance with chemicals to increase the performance of the well-flows back out of the well after it interacts with the rock formation. "Often in Alberta, the water becomes super-saline, sometimes five to 10 times as salty as ocean water. The proper handling, treatment and disposal of this flowback water is an area that merits further investigation."

To examine the potential environmental impacts of surface spills and uncover new methods for flowback treatment and reuse, he is collaborating closely with U of A colleagues Greg Goss (biological sciences) and Jonathan Martin (laboratory medicine and pathology), experts in aquatic toxicology and analytical organic chemistry, respectively.

"Our research program is extremely mechanistic. We want to know if this water is potentially toxic. If it is, we want to understand the fundamental reasons behind its toxicity and what the impacts to ecosystems might be if it is spilled at the surface."

Understanding potential hydraulic fracturing impacts

The primary goal of this research is to further understanding of the full spectrum of potential impacts associated with fracturing. Additional benefits of the five-year study will be to reduce fresh water use in hydraulic fracturing and share best practices with industry through scientific publications and public forums.

"There are two ends of the spectrum-people who think hydraulic fracturing should never happen and those who think fracturing operations come without environmental consequences," says Alessi. "My view is more pragmatic. At least in the foreseeable future, hydraulic fracturing is going to happen. While it is happening, let us work to address some of these potential concerns. Ultimately, we want to improve the water cycle and mitigate water use and the potential environmental impacts. I hope the information we produce is useful to policy-makers, the public and our industrial partners."

"Encana is pleased to support science-based independent research through Canada's academic institutions. It is through partnerships, such as the UAlberta Chair in Water Resources, that we progress the responsible development of Canada's abundant oil and gas resources," says Richard Dunn, vice-president of government relations with Encana.

The study, "Informing best practices for hydraulic fracturing in Alberta: Water sources and characterizing the toxicity of produced fracturing fluids," was approved for a nearly $1-million collaborative research and development grant through the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. Industry partner Encana also contributed more than $1 million to the study over the next five years.