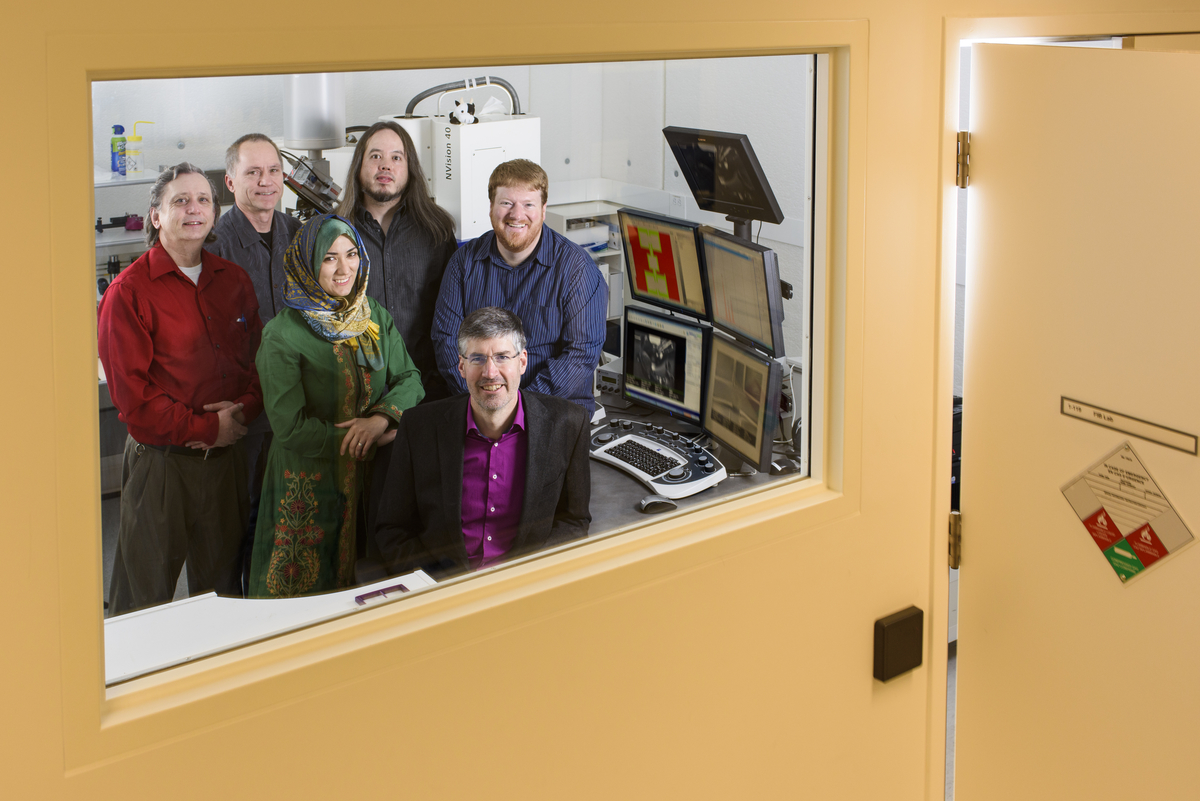

Mark Freeman (seated), with Fatemeh Fani Sani (middle row left), Joseph Losby (top right) and team members have discovered a route to lab-on-a-chip technology for magnetic resonance, a tool to simplify advanced magnetic analysis for device development and interdisciplinary science.

A garnet crystal only one micrometre in diameter was instrumental in a University of Alberta team of physicists creating a route to "lab-on-a-chip" technology for magnetic resonance, a tool to simplify advanced magnetic analysis for device development and interdisciplinary science.

"To most, a gem so tiny would be worthless, but to us, it's priceless," says Mark Freeman, University of Alberta physics professor and Canada Research Chair in condensed matter physics. "It was the perfect testbed for this new method."

In the new method of measuring magnetic resonance, published in the November 13, 2015 issue of the journal Science, the signal is a mechanical twisting motion, detected with light. The new approach is more naturally suited to miniaturization than the current method, which creates an electrical signal by induction. In fact, the entire magnetic sensor unit created with the new technology can fit on a chip as small as one square centimetre.

"Working in condensed matter physics is like having the best seat at an awe-inspiring parade of progress." -Mark Freeman

"Our discovery makes the case that magnetic resonance is in essence both a mechanical and magnetic phenomenon on account of magnetic dipoles possessing angular momentum," says Freeman, noting that the concept of magnetism makes more sense when you consider its mechanical properties. "Magnetism needs better spin doctors than it has had. Everything in the world is magnetic on some level, so the possibilities for scientific applications of this new technique are endless."

A world of miniaturized possibilities

This animation shows how frequency-mixing works. Using the example of a moving peg on a rotating slider in a disk, waves are illustrated as rotations.

The discovery opens up a world of possible miniaturized platforms for health care, technology, energy, environmental monitoring, and space exploration. Explains Freeman, "There are immediate applications in physics, Earth sciences, and engineering, but we have only looked at electron spin resonance. Proton spin resonance is the next big step that will open up applications in chemistry and biology."

To foster the development of these applications, Freeman's team plans to openly share the information about how to execute this technique, feeding the current maker movement. It was important to the team not to patent this discovery-as is often the pressure for scientists conducting these types of discoveries-but instead to publish their findings in a scientific journal to provide open-source access that will advance the field. "Ultimately, the way science makes progress is through people sharing discoveries," says Freeman, adding that he hopes others will adapt the technology for their own needs.

Lab-on-a-chip technology

In this large-scale model of the nanomechanical torque sensors developed by UAlberta researchers, the steel disk is 31 millimetres in diameter. The model is 10,000 times larger than the nano-scale version of the sensor.

Freeman, who worked for IBM before coming to the University of Alberta, believes that chip-based miniaturizable mechanical devices-by virtue of their small scale and superior performance-will come to replace some electronic sensors in devices like smart phones and on space exploration probes. "It's an elegant solution to a challenging problem, simple but not obvious," says Freeman, who has been working on the experimental challenge solved in this paper for the past two decades. "Working in condensed matter physics is like having the best seat at an awe-inspiring parade of progress."

Postdoctoral fellow Joseph Losby, PhD candidate Fatemeh Fani Sani, and former undergraduate student Dylan Grandmont spearheaded the research under the guidance of Freeman, along with collaborators at the National Institute for Nanotechnology and the University of Manitoba. The findings, "Torque-Mixing Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy," were published in the journal Science.