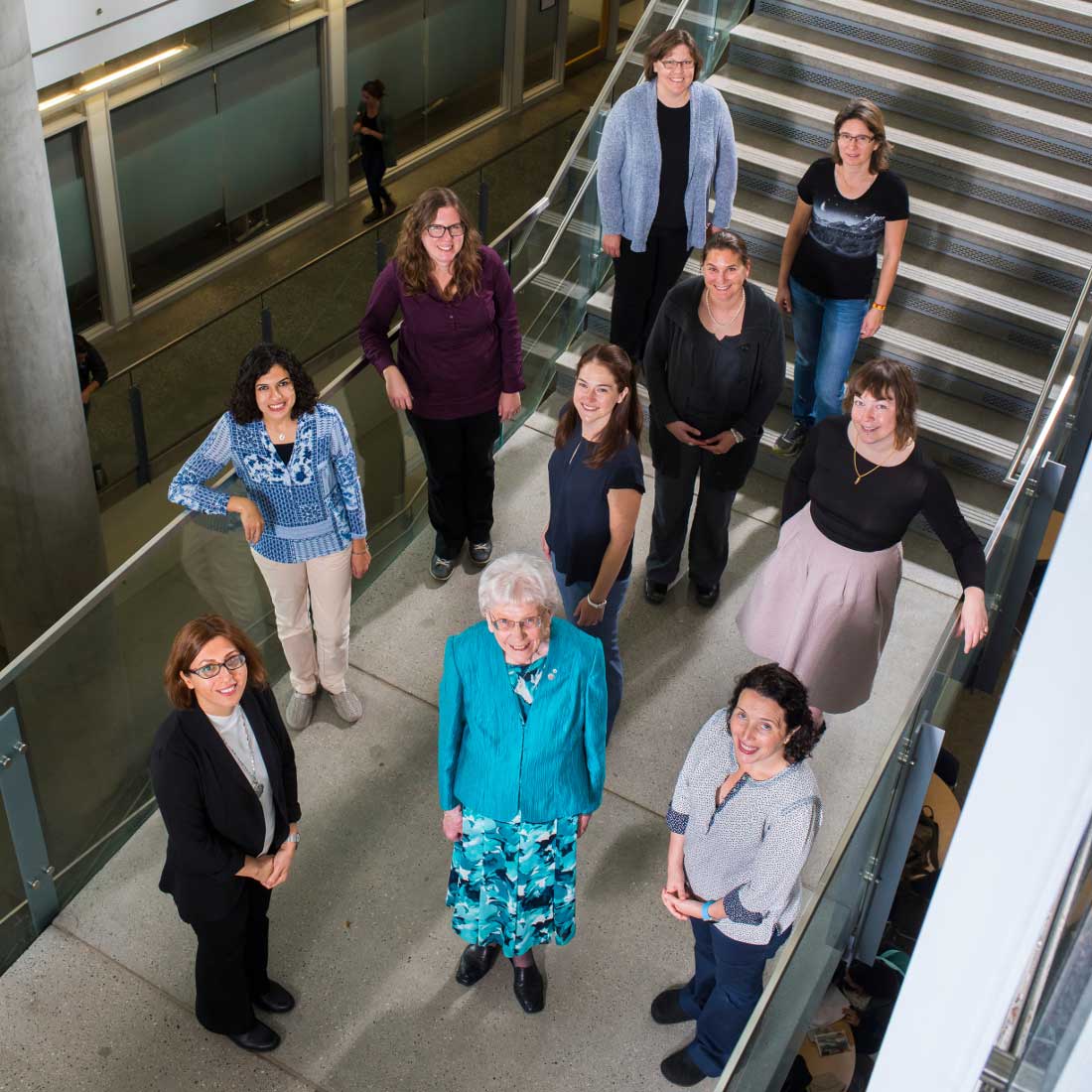

Margaret-Ann Armour (centre) with nine of the 14 female faculty members hired during her tenure. Top row L to R: Claire Currie, Natalia Ivanova; Second row from top L to R: Lindsay LeBlanc, Jocelyn Hall; Second row from bottom L to R: Sarah Nadi, Florence Williams, Sarah Styler; Bottom row L to R: Monireh Faramarzi, Margaret-Ann Armour, Rebecca Case.

In 2004, Gregory Taylor, then dean of the U of A's Faculty of Science, discovered that even though more than 50 per cent of the undergraduate science population was female, women made up only 14 per cent of faculty numbers. Not only that, but that percentage hadn't changed in seven years.

To remedy the situation, Taylor created the position of Associate Dean (diversity). Margaret-Ann Armour ('70 PhD, '13 DSc)-an experienced champion of women in science who taught in the Department of Chemistry for nearly 30 years-was appointed to the position in 2005.

"I was just getting ready to retire," recalls Armour. "I already had a list of things I wanted to do in my retirement. One of them included encouraging women in science and engineering, and since this position supported my goal, I decided to take it."

Given that there are fewer women than men in the sciences, those women at the top of their game are usually also in high demand by schools other than the University of Alberta.

Armour wasn't starting with a blank slate. She had previously founded the Women in Scholarship, Engineering,Science, and Technology (WISEST) program in 1981 and served on the board of the Canadian Centre forWomen in Science, Engineering, Trades,and Technology (WinSETT) since 2010. These experiences, plus her knowledge of the research on women in science, gave her a solid foundation from which to develop a diversity program.

Armour's first step in her new role was to create Project Catalyst, a series of 13 initiatives designed to increase the diversity of the Faculty of Science, from identifying strong female candidates for individual positions and personally inviting them to apply, to lobbying for adequate high-quality daycare spaces on or near campus, to implementing a mentoring program for new female faculty.

It's an ambitious program: since 2005, Armour has overseen the hiring of 14 women out of 37 faculty positions in total-almost 40 per cent. During this time, the university also hired its first woman in computer science in 18 years-a highly sought-after software engineer, Sarah Nadi, who started in the summer of 2016.

However, 11 years after Armour was hired, the overall percentage of female faculty has increased to only 15 per cent total.

"If there were only one or two problems keeping us from getting more women on faculty, we'd have solved them by now. But it's much more complex than that."

"What this highlights is that gender diversity is a multi-faceted problem," says Armour. "If there were only one or two problems keeping us from getting more women on faculty, we'd have solved them by now. But it's much more complex than that."

First of all, it's difficult to find women who are even interested in taking on faculty positions. "When I talk to female graduate and postgraduate students, I'm disappointed to hear that many of them aren't interested in an academic career," she says. "They don't want the lifestyle that their supervisors have."

Given that there are fewer women than men in the sciences, those women at the top of their game are usually also in high demand by schools other than the University of Alberta. "These are top-notch researchers," says Armour. "They often have competing offers from other universities."

It can also be difficult to convince some of the candidates to move to Edmonton, an unfamiliar city without the cachet of Toronto or cities in Europe or the U.S. "To counter this, we try to bring on women who have some connection to the city," explains Armour. "They may have done one of their degrees here or have family here."

Then there is the problem of retaining those women who are already on staff, as they are often recruited by other universities. "In the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, for example, we had six women faculty but lost three between 2013 and 2015," says Armour. The Department of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences was similar, with its six female faculty in 2009 dropping to three in 2016.

"We're recognizing that, while we're a research- intensive university, we're here because of students. If we bring in someone who can't connect with undergrads, we're not doing the university a service."

There are positive trends too, however. "The selection committees are now completely committed to increasing diversity," says Armour. "They're more proactive."

The committees are more aware of things such as the inherent bias in reference letters written for women versus men and take into account more than just research ability when evaluating an applicant's CV. "We're recognizing that, while we're a research-intensive university, we're here because of students. If we bring in someone who can't connect with undergrads, we're not doing the university a service," says Armour.

While more work remains to be done, Armour feels that her diplomatic approach to the problem is paying dividends. "I ask committee members questions rather than telling them how to do things," she says. "I don't tell them they're doing things wrong. I ask them to be aware of the influences on women when they're making decisions. Seeing such a huge change in their attitudes really makes me feel like things are improving."

If the university can keep up its rate of hiring 40 per cent female faculty and encourage existing female faculty to stay, they'll be on track to significantly increase the number of female faculty in the Faculty of Science, a positive for the entire University of Alberta campus.

Sarah Boon ('05 PhD) spent seven years as an environmental science professor. Her articles about academic culture, women in science, nature, and the environment have been published in print at Outpost, BC Forest Professional, and iPolitics, and online at Canadian Science Publishing, the Nature Conservancy of Canada, and the Canadian Science Writers' Association. She has forthcoming work at CBC's The Nature of Things and Terrain. org. Sarah is a co-founder and serves on the board of directors of Science Borealis, where she was the earth & environmental science editor. Find her at Watershed Moments or on Twitter @SnowHydro.

Inspiring the Next Generation of Students

Dr. Margaret-Ann Armour School opens in Edmonton's southwest

For more than a quarter of a century, Margaret-Ann Armour has been Canada's premier ambassador of science, volunteering tirelessly to raise national awareness among school-aged girls, educators, parents, and employers of the importance of encouraging women to enter science and engineering. In recognition of Armour's exemplary contributions to the community and lifelong dedication to learning, the Edmonton Public School Board has bestowed its highest honour on this indefatigable leader, naming one of its newest schools in her honour. The Dr. Margaret-Ann Armour School- which opened this fall in Edmonton's Ambleside community to serve students in kindergarten through grade 9-was named to serve as inspiration for the 600 students and teachers who will roam the new halls. Armour remains active in her engagement of grade-school students in both urban and rural settings. "I want kids to have fun with science," she says. "That's what keeps them interested." Armour was on hand on the first day of school to welcome students and teachers to the new year and did her best to greet every single one of them with hugs, handshakes, and words of encouragement.