The Captain and the Mad Hatter

In creating the University of Alberta, both Premier Alexander Rutherford and President Henry Marshall Tory envisioned a single, non-denominational and democratic institution that would serve all Albertans. Many are familiar with Tory’s first convocation address in 1908, and his belief that knowledge, transmitted through the modern state university, should uplift the whole people. Fewer know that, two years earlier, the University Act declared that “no woman shall by reason of her sex be deprived of any advantage or privilege accorded to male students of the university.”

Seven women were part of the U of A’s inaugural class in 1908. They called themselves the “Seven Independent Spinsters.” Many of the first female students made an immediate impact. Decima Robinson was the first student to receive an undergraduate degree. Jennie Stork Hill was the first to receive a graduate degree, and became the second woman in Edmonton to hold municipal office.

Despite this, it would be erroneous to say that the conditions for women in the early days of the U of A were idyllic. The Persons Case was still 20 years away. The Wauneita Society, the university’s all-women’s club, used racist stereotypes in their traditions and rituals. And even though there was great interest and excellence in women’s sports, it wasn’t until 1919 that the Women’s Athletics Association secured its independence as a student club. The goal of equality between the sexes simply did not correspond to the realities of life in the early 20th century.

Bold Beginnings

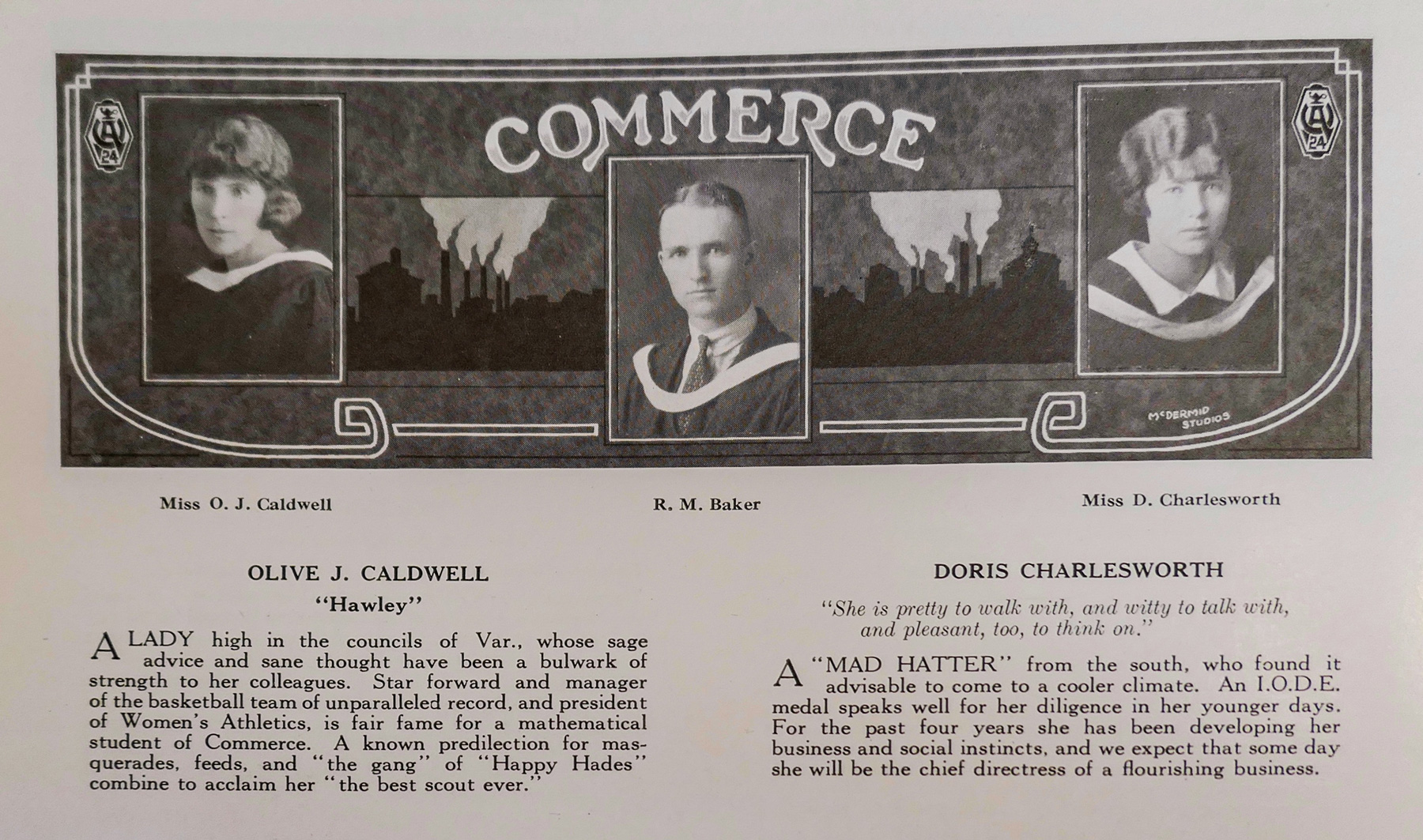

The Alberta School of Business officially began in 1916 as the Department of Accountancy. By 1919, students could graduate from the U of A with a Bachelor of Commerce degree, but it was not until 1923 that the first three grads arrived at Convocation. All three were men. A year later, however, two women crossed the stage to receive their Commerce degrees. The U of A’s 14th annual convocation was already set to be a memorable ceremony. Over 200 students would receive a degree, one of the largest graduating classes in the university’s short history. A doctoral degree was also going to be conferred to the university’s biggest academic star, James Bertram Collip, co-discoverer of insulin. But when Olive J. Caldwell and Doris Charlesworth crossed the stage in Convocation Hall on May 15, 1924, they were, perhaps wittingly, blazing a trail for thousands of young businesswomen who would follow in their footsteps.

Olive Caldwell, R.M. Baker, and Doris Charlesworth, three of the seven students who graduated with a Bachelor of Commerce degree in 1924. Image taken from the 1923-24 edition of Evergreen and Gold.

Both Olive Caldwell and Doris Charlesworth began their studies at the U of A in 1920. Given what is known of the BCom program at the time, they would have followed the same academic route. First-year courses were “as for B.A.,” meaning both would have taken the same common year courses as every other student in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (a mix of language, literature, history, mathematics, natural sciences, and physical education). Second-year would see the introduction of a couple courses in accounting and political economy. In their third and fourth years, students were fully immersed in business classes, including finance, business administration and marketing, commercial law, insurance, and economics.

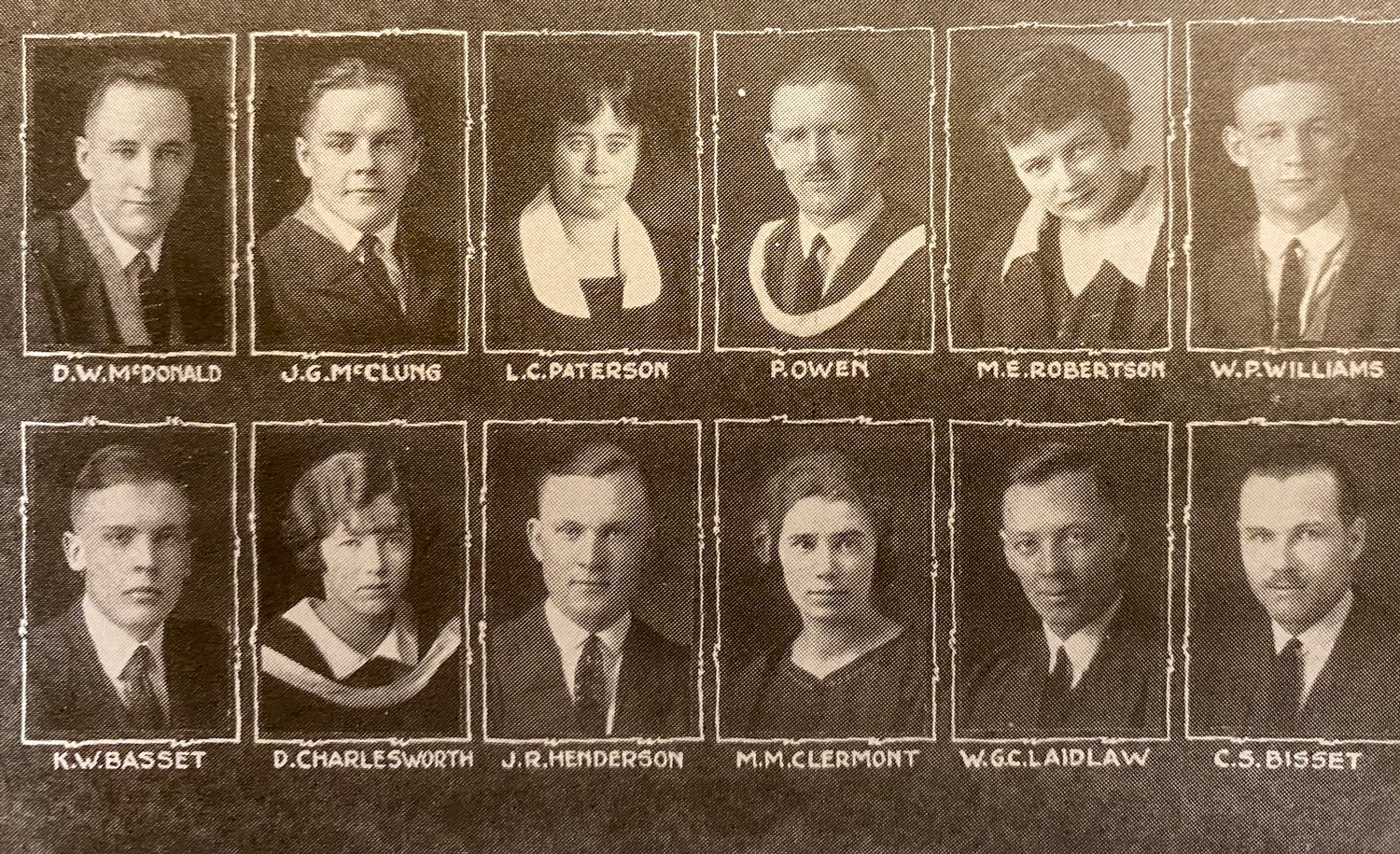

Other than the knowledge that they would have taken courses together, there isn’t much visible overlap in the lives of the two women. Both were members of the Commerce Club in their final year (Caldwell was vice-president). Both were thanked by Gateway staff for contributing to the newspaper that same year. Otherwise, the records highlight two very different stories: one a superb athlete and active participant in campus life, and the other a young woman involved in a prominent charitable organization and Edmonton’s larger social scene.

The Mad Hatter

In her graduation write-up, Doris Charlesworth is identified as a “Mad Hatter from the south.” What at first seems an evocative description unfit for its time is actually something much more mundane. Charlesworth was from Medicine Hat.

Doris was the daughter of Lionel and Gertrude Charlesworth. Lionel was a longtime civil servant in Alberta, beginning as a land surveyor in Medicine Hat before moving his family to Edmonton. In 1905 he was named Alberta’s first director of surveys, and in 1915 became Deputy Minister of Public Works. In 1924 Lionel became president of the Association of Professional Engineers and Geoscientists of Alberta (APEGA), and in 1950 he received an honorary degree from the University of Alberta. A neighbourhood in southeast Edmonton bears his name.

Doris Charlesworth, bottom left, and fellow members of the 1923-24 Commerce Club. Image taken from the 1923-24 edition of Evergreen and Gold.

Lionel was a frequent visitor to the U of A campus, giving talks to students and keynote speeches at Engineering dinners. Doris’ brother Gerald attended the U of A alongside her, sitting on Student Council in 1920-21 and completing the 4-year medical degree the same year Doris completed her commerce degree. A note in a 1922 edition of The Gateway indicates Doris ran for her Junior Class executive (she lost), but it is in The Edmonton Bulletin where we find her name most mentioned.

Charlesworth’s name pops up often in the "Social Side of City Life" section of the Bulletin. In many ways, social sections in early 20th century newspapers were the precursor to today’s gossip websites and social media platforms. Readers would be kept up-to-speed on the latest parties, weddings, and social club activities, as well as the names of all the very important people in attendance. During her time in high school and at the U of A, Charlesworth’s name often appears. She attended house parties, several tea dances, bridge tournaments, and even co-hosted a Valentine’s Day party in 1922.

Charlesworth went to Victoria High School, and is listed as an attendee at the school’s inaugural “Conversazione” in 1919. It is at Victoria that Charlesworth also received a gold medal from the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE). Founded in 1900 as a way for women to support the British Empire and its soldiers, IODE still exists today as a charitable organization dedicated to education, citizenship, and community service. Charlesworth was elected second vice-regent of the Lady Patricia Ramsay chapter in 1921. It was a youth chapter initiated under the auspices of the larger Edmonton chapter, and membership consisted of women from high school and university. The philanthropic work of the IODE across Canada was impressive for its time, and meaningful. They created memorial funds for the children of veterans killed or disabled in the two World Wars, raised money for supplies to be sent overseas, and even built and operated the library in Stettler, Alberta.

On June 25, 1925, at All Saints Cathedral, Charlesworth married Sidney Bruce Smith. Smith, who graduated with his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1919, and received a Law degree in 1922, had a long and successful career in Edmonton, which contributed to him receiving an honorary degree from the University of Alberta in 1962. A junior high school, S. Bruce Smith, in west Edmonton, is named in his honour.

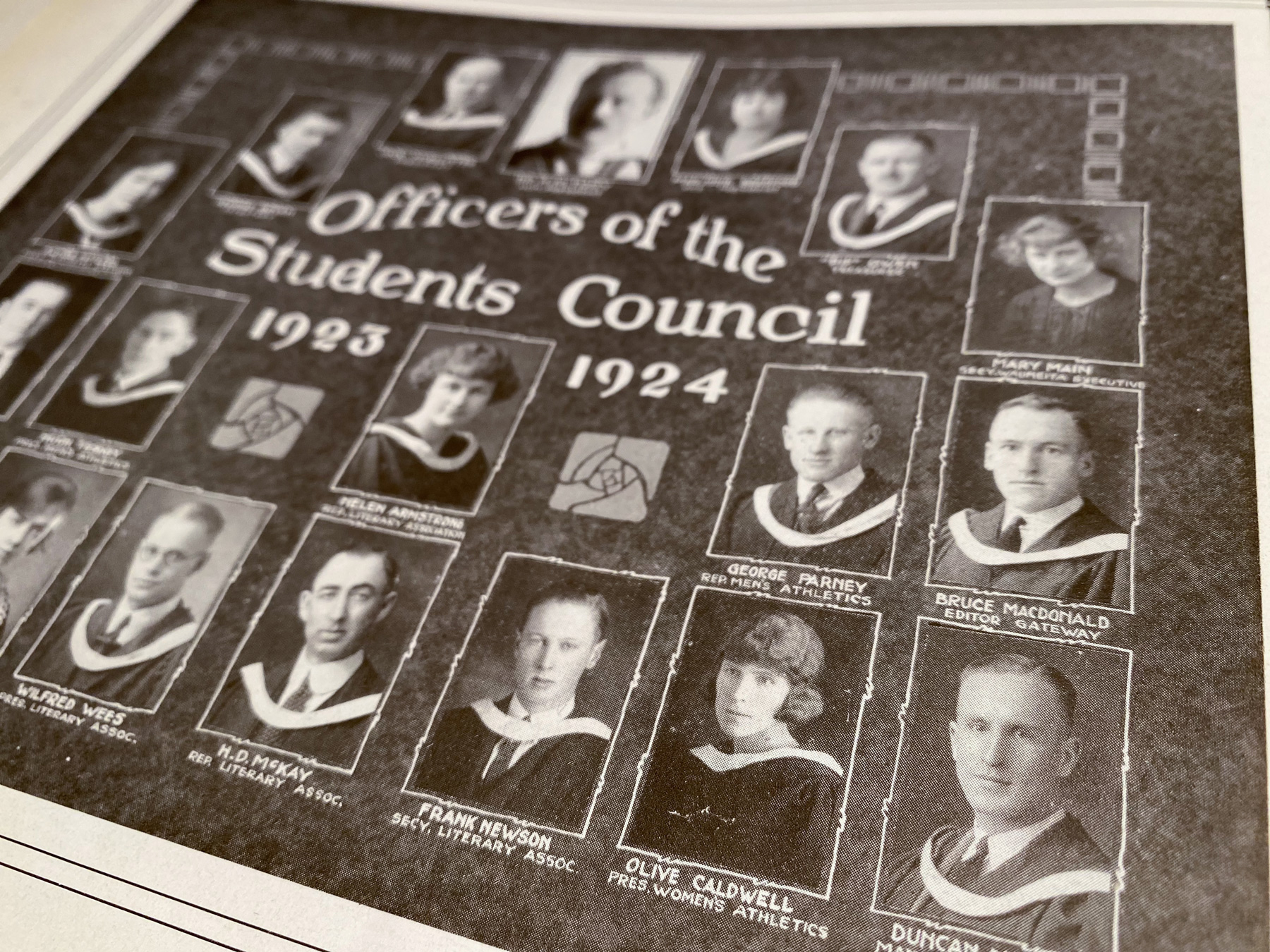

The Captain

In contrast to Doris Charlesworth, the campus life of Olive Caldwell is well documented. She lived in Athabasca Hall, the U of A’s first building and residence. She began her involvement with the Women’s Athletics Association in her second year, taking on the positions of secretary, treasurer, and eventually president. Her role on the Association meant Caldwell was also a member of the Students’ Union executive, and reports from The Gateway indicate that she wasn’t shy about speaking her mind.

In October 1923, the SU debated its annual budget. As disagreement arose around the decision to buy new bleachers for the gymnasium, a third-year student, Joe O’Brien, complained that the Women’s Athletic Association was not paying its fair share for the bleachers. Caldwell, “aroused by these reflections on her sex, took issue with Mr. O’Brien and proceeded to deal with his arguments in a very destructive manner, and apparently vindicated her position, for no one seemed disposed to continue the argument.” Thankfully for O’Brien, an Arts student and rugby/hockey player named Clarence Campbell redirected the discussion back to the larger question of the SU’s reserve fund.

Olive Caldwell, bottom right, and other Students’ Union executive officers. Image taken from the 1923-24 edition of Evergreen and Gold.

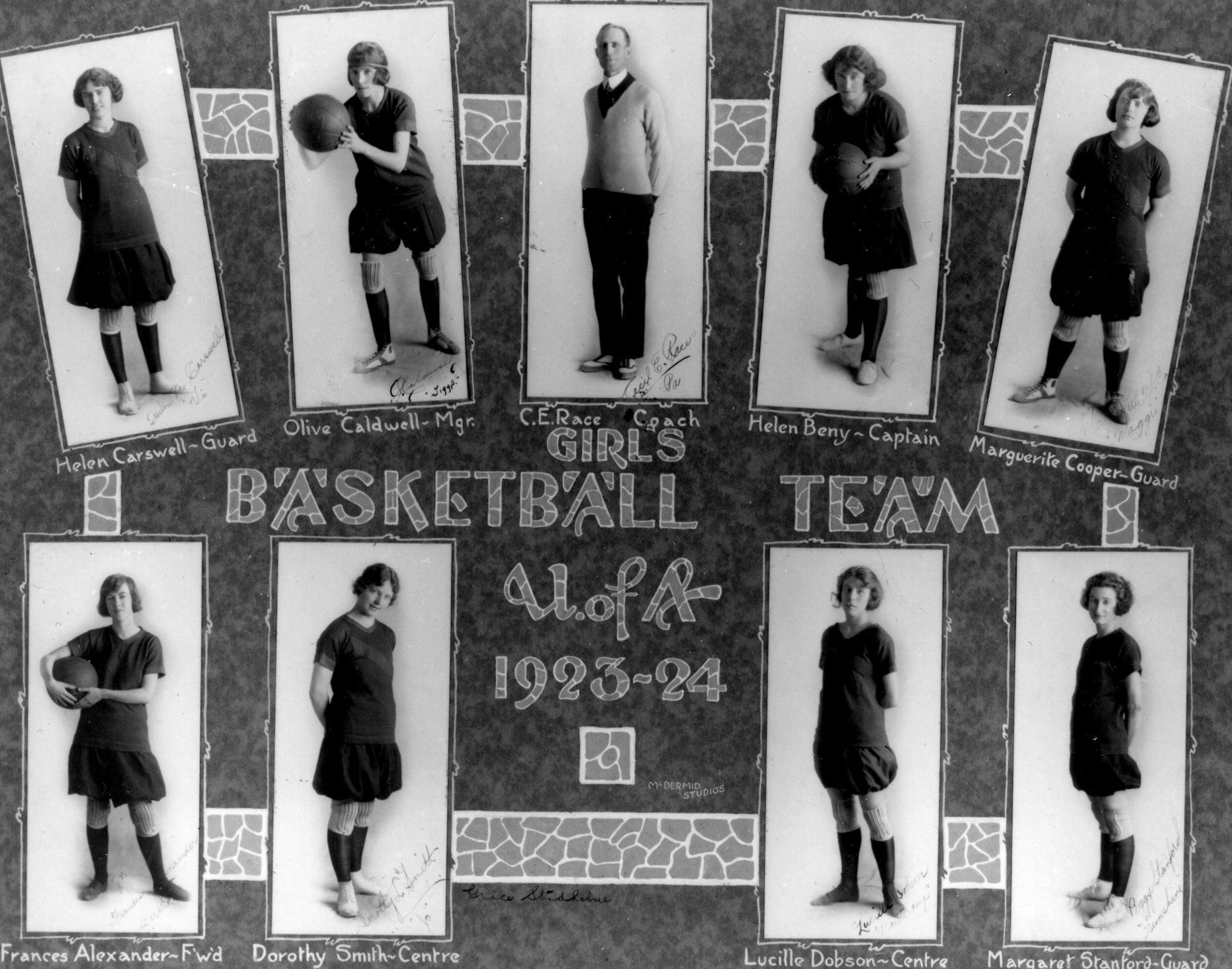

Refusing to give ground to an opponent was a skill Caldwell would have learned in the gym and on the field. By her second year, she was helping plan track meets, playing tennis, shot putting, and running the 50-yard dash. She was also a forward on the women’s basketball team, competing against one of the greatest teams in the history of sports, male or female, amateur or otherwise. That team was the Edmonton Grads.

The Edmonton Commercial Graduates Basketball Club—better known as the Edmonton Grads—was established in 1915 under the direction of a high school teacher named John Percy Page. Over the next 25 years the Grads would win over 400 games, compared to only 20 losses. They held the national title from 1922-1940, won the Underwood International Trophy (USA-Canada) every year from 1923-1940, and were undefeated in 24 exhibition games at the 1924, 1928, and 1936 Summer Olympics (women’s basketball was not declared an official Olympic sport until 1976). They were World Champions, and their reputation as one of the most dominant teams in the history of sport remains to this day.

As early as 1916, the Grads were playing in an intercollegiate league with the U of A’s women’s basketball team, known simply as Varsity. Both the Grads and Varsity were known for blowing other teams out—a Commerce Club column in the February 5, 1924 edition of the Gateway welcomes Caldwell and sophomore May Cooper back from a successful road trip, greeting them as “conquerors who have indeed wrought havoc in hostile camps abroad”—but when they played each other the games were almost always highly competitive and evenly matched. The two teams would often face each other in provincial or western Canadian finals matches, and though rare, it was not inconceivable for Varsity to steal a game or two from their legendary counterparts.

Olive Caldwell, top left, and the 1923-24 women’s Varsity basketball team. Image courtesy of U of A Archives, UAA-1972-056-044.

Caldwell was a forward on the Varsity team for three years, beginning in 1921. The team lost the City Championship to the Grads 21-10 that year, though Caldwell played well, leading Varsity with 8 points. In 1922-23, Varsity won the Inter-Varsity and Inter-Collegiate championships, losing the Provincial title to the Grads. In October 1923, the beginning of her last season, Caldwell was named captain of the Varsity team. Varsity finished the season undefeated, again winning the Inter-Varsity title. One of the “greatest basketball machines to ever represent the University of Alberta” was now ready to face the Grads for the provincial championship.

On March 27, 1924, Caldwell played her last game for Varsity. The team lost both matches in their series against the Grads, 28-13 and 21-15. Despite the defeat, The Gateway was effusive in their praise for Varsity. “Seldom have two more evenly matched teams than the Commercial Graduates and the U of A Women’s Basketball team been seen in action” remarked the paper. “For close checking, brilliant dribbling and phenomenal shooting the game was the equal, if not the superior, to any basketball game ever played in Edmonton...Varsity as a team turned in a wonderful performance.”

Caldwell only scored two points in her final game, a disappointing end for one of Varsity’s star players. Almost a year later, however, Caldwell got her revenge. On March 6, 1925, in what The Gateway called “one of the greatest women’s basketball games ever staged,” a team called the Varsconas defeated the Grads 22-18, one of only 20 losses the Grads would ever experience, and their first loss in 42 games. The Varsconas were a combined team, made up of former Varsity players as well as players from Strathcona High. Olive Caldwell was on the winning team.

This story paints an incomplete picture of Olive Caldwell and Doris Charlesworth. Until now, neither has featured prominently in any University of Alberta or School of Business history. What we know about Doris mostly relates to the men in her life. We know more about Olive’s personality and interests thanks to her involvement in student clubs and athletics, and the consequent coverage by the U of A’s student newspaper, The Gateway. Yet even those stories do not tell the full tale.

If you are a descendant of Olive Caldwell or Doris Charlesworth, and have more information about their lives before, during, or after graduating from the U of A, we would very much like to hear from you. Please email us at asbmcom@ualberta.ca, and help us complete the story of these two remarkable women.