Diabetes patients, researchers, donors and funders will gather this week at the Alberta Diabetes Institute to celebrate 25 years since the Edmonton Protocol was first published by a team of University of Alberta researchers in the New England Journal of Medicine. Edmonton’s islet cell transplant program has since grown into one of the world’s largest and most successful.

It was a life-saver for Yukon patient Rebecca Kalles Meng, now 61, who has lived with Type 1 diabetes since she was five years old. Her disease became increasingly difficult to control, and she would end up in hospital regularly. She could no longer live alone.

Five years ago, she received two transplants of insulin-producing islet cells into her liver under the Edmonton Protocol.

“My whole world changed after the transplant. My blood sugars stabilized, and I no longer needed someone with me all the time,” says Kalles Meng. “I now have my own life, and I have freedom. It makes me feel so good. It literally saved my life.”

Before the Edmonton Protocol, 293 patients around the world had received islet transplants, but only eight per cent remained insulin independent. The U of A team focused on better ways to prepare sufficient islets, transplant without surgery and care for the patients afterwards, in particular developing a unique regime of anti-rejection drugs.

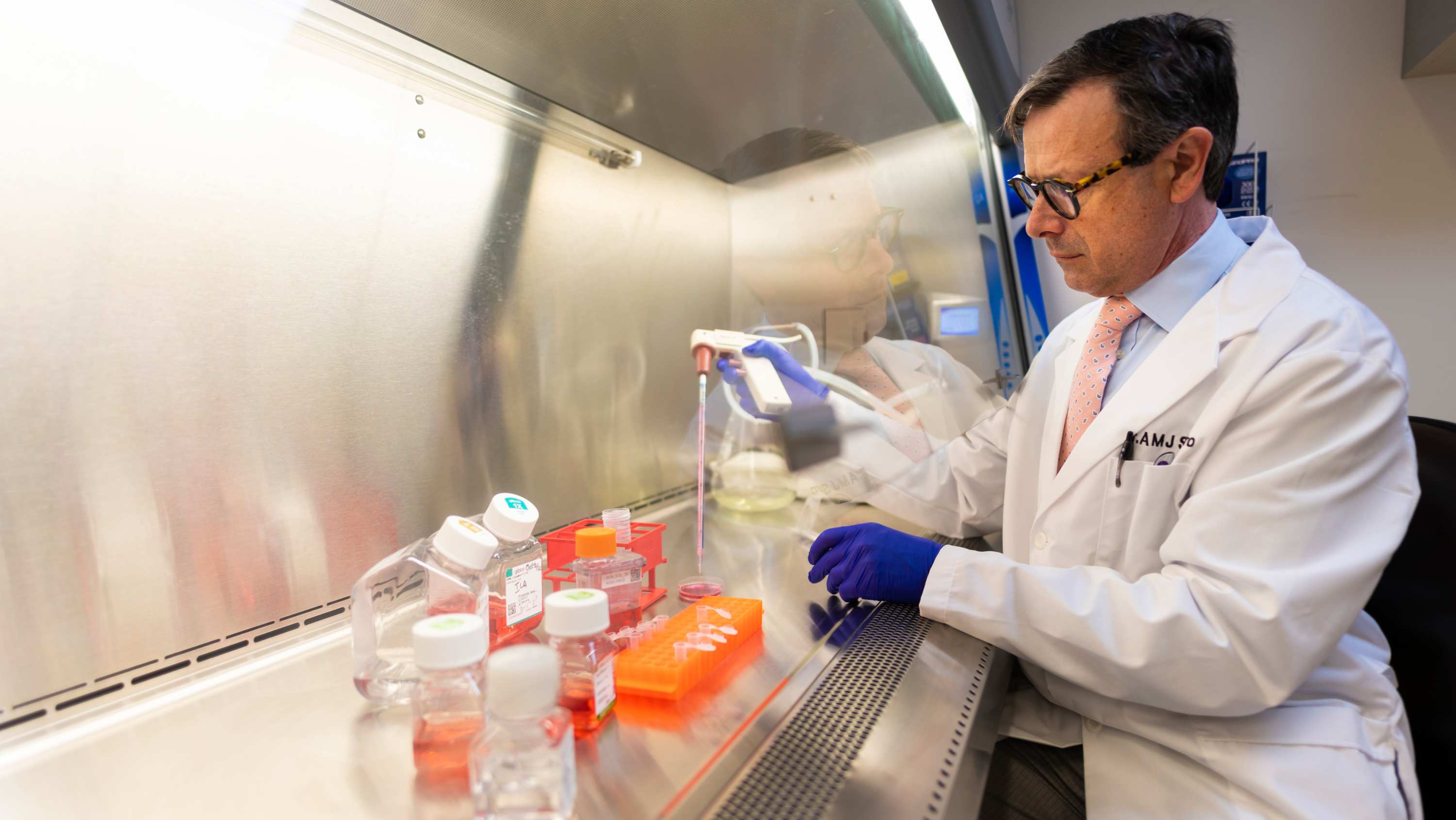

“The Edmonton Protocol evolved out of desperation as a last-ditch attempt, and honestly I did not think it would work!” recalls James Shapiro, professor of surgery, Canada Research Chair in Transplantation Surgery and Regenerative Medicine and lead author on the original paper. “When the seventh patient was insulin-free with excellent sugar control, it was clear we had something special — and strikingly different from what had gone before.”

“Today, more than 3,000 islet transplants have been carried out worldwide, and more than anything, patients and their families have real, tangible hope of a better quality and longer life ahead,” Shapiro says. “I am so proud of our clinical research team that made this happen and has made a difference.”

On March 11, 1999, Byron Best, a teacher from the Northwest Territories, became the first patient to receive a transplant following the new approach. Within a week, he no longer needed insulin injections. Six more patients soon followed, and the team knew they had a breakthrough.

Since then, 330 patients have received nearly 750 transplants in Edmonton.

“It’s impossible to overstate what a game changer this has been for people living with complex diabetes,” says Brenda Hemmelgarn, dean and vice-provost of the College of Health Sciences and dean of the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry.

“Edmonton’s clinical islet transplant program quickly became the world’s largest islet transplant program and cemented our reputation as a leader in diabetes research. Today, that work continues to grow and evolve.”